Routledge har skapat en olympisk temasida där man samlar artiklar och böcker ut förlagets omfattande idrottsforskningsutgivning kring ett visst tema.

Topic of the week: Olympics before Coubertin

Topic of the week: Olympics before Coubertin

by Martin Polley, University of Southampton, UK

Twitter: @MartinPolley2

If the Olympic Games were started from scratch today, I would bet my life savings on the fact that they would not be named after a pagan festival that died out in 393 AD. Yet when Pierre de Coubertin and his colleagues founded the International Olympic Committee in 1894, and staged their first Olympic Games in 1896, that is exactly what they did. We cannot understand the modern Olympic Games, with their philosophy, their religious trappings of creeds, oaths, and ceremonies, and the very fact that they bear this antique name, unless we look to the context in which Coubertin was working.

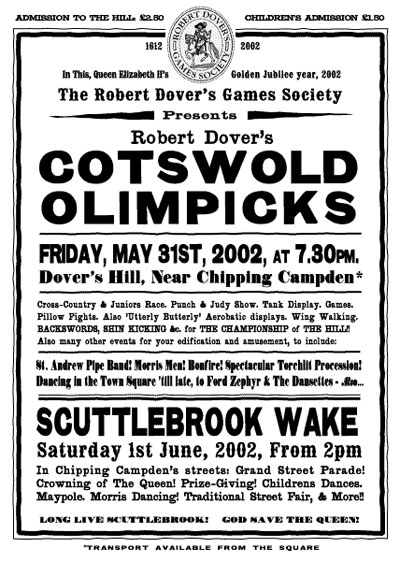

Coubertin’s version was one among many sporting festivals of the nineteenth century that borrowed names, images, and vocabularies from the ancient Olympic Games. This was, after all, a time when many people looked to the classics for their inspiration, as seen in so much art, architecture, and literature of the time. Add to this classicism a specific knowledge of ancient Olympia, fed by Richard Chandler’s discovery of the site in 1766, and by Blouet and Curtius’ excavations of the site over the course of the nineteenth century, and we can see why so many people called their games Olympic and Olympian. The Wenlock Olympian Games, the Liverpool Olympic Festivals, the Shropshire Olympian Games, the National Olympian Games, and the Morpeth Olympic Games, which all started between 1850 and 1880, were part of this trend. Alongside these Victorian projects were the famous Cotswold Olimpick Games, which had started life as an anti-puritanical Whit festival in the early seventeenth century, and which lasted until 1850. Coubertin, crucial as he was in bringing internationalism into the mix, was thus part of a disparate trend.

As a historian of these pre-Coubertin Olimpick, Olympic, and Olympian events, I am often asked what was Olympic about them. I like to turn this question around, and ask what is Olympic about what we saw in London in 2012, or about what we will see in Sochi in 2014. There were no nude athletes at London 2012, and there will be no sacrifices to Zeus at Sochi. By exploring the sporting festivals covered in these articles, we can get a sense of perspective on the modern Olympic Games and why they have this name from deep in classical past.

Featured articles

Introduction: Britain, Britons and the Olympic Games

Martin Polley

FREE ACCESS

The curious mystery of the Cotswolds Olympicks

Jean Williams

Olympus in the Cotswolds: the Cotswold games and continuity in popular culture, 1612–1800

Simone Clark

An indifferent beginning (Prologue to International Journal of the History of Sport Special Issue: Rule Britannia–Nationalism, Identity and the Modern Olympic Games)

Matthew P. Llewellyn

The Regular Re-Invention of Sporting Tradition and Identity: Cumberland and Westmorland Wrestling C.1800–2000

Mike Huggins

The origins of the modern olympics: a new version

David C. Young

Visiting the Olympic Games in Ancient Greece: Travel and Conditions for Athletes and Spectators

N. Crowther

Mens Sana in Corpore Sano? Body and Mind in Ancient Greece

David Young

Athleticism and antiquity: symbols and revivals in nineteenth‐century Greece

Christina Koulouri

Featured Books and Chapters

Rule Britannia: Nationalism, Identity and the Modern Olympic Games

Matthew P. Llewellyn

This Great Symbol: Pierre de Coubertin and the Origins of the Modern Olympic Games

John J. Macaloon

The History of Sport in Britain, 1880-1914

Martin Polley

Moving the Goalposts: A History of Sport and Society in Britain since 1945

Martin Polley