Hans Bolling

PhD in History, Independent scholar

Histories of Women’s Football in Britain and Ireland

332 pages, paperback, ill

Oxford, Oxon: Peter Lang Publishing 2025 (Sport, History and Culture)

ISBN 978-1-80079-946-2

Even for someone sitting in Sweden, it is clear that women’s football has grown in popularity in England over the past decade. I am not thinking primarily of the interest in women’s football in connection with major tournaments, when national glory can be won, interest in all forms of sport seems to increase, but rather on interest in everyday football. Newspapers are writing more about it, podcasts are recorded and more and more people are turning up to watch club games, and as an icing on the cake more and more prominent players from the rest of the world are representing English clubs.

But it is not just in women’s football that interest is increasing, the same can also be said about the men’s game. During the 21st century football has become so popular that you have to opt out if you do not want to take an interest in the game, which was not the case when I was growing up. I am not willing to go so far as to say that football has taken the place of religion in society but something has happened.

The publication of Histories of Women’s Football in Britain and Ireland, edited by Fiona Skillen, Helena Byrne and Gary James bears witness to the above-mentioned observation. So why choose to publish an anthology with histories of women’s football right now? In this case, there seem to be three in no way contradictory reasons: (1) The growing public interest in Britain in women’s football which is exemplified by the European Championship played in England in 2022 and rise of Women’s Super League; (2) the growing momentum around research into the history of women’s football, which has received a boost from the rapid digitization of old newspapers in the last decade, which has made much previously inaccessible source material easily available to researchers; and (3) anniversaries and jubilees, such as the centennial of FA’s ban on women playing football on pitches of the members of the association in 1921 and the fiftieth anniversary of the lifting of the ban.

However, in this section I am missing a chapter about an important and somewhat buried event. That is, a chapter on the “World Cup tournaments” played in Italy in 1970 and in Mexico in 1971, organised by the privately funded Federation of Independent Female Football.

Histories of Women’s Football in Britain and Ireland is an edited book which according to the introduction “draws together both regional and national studies to provide a more nuanced understanding of the history of the women’s game in Britain and Ireland than has been possible before” (pp. 2–3). And this makes it an interesting and readable book, but it also contributes to a lot of repetitions that could have been avoided if the editors had been somewhat more definite in exercising their editorial prerogative. In total the book contains 18 empirical chapters divided into five sections: ‘Pre-1900’, ‘First World War’, ‘Post Second World War’, ‘International Perspectives’, and ‘Representing Women’s Football in Culture’.

In the first three sections of the book new findings around the development of women’s football is presented and explored, readers are presented with examples of women playing football, early examples primarily from Scotland but also in Northern England and Wales. In the second section the reader is taken to the other side of Irish Sea. The second section also rewards the reader with an excellent chapter about the phenomenon that more than any other influences the content of almost all the chapters in the anthology: The English FA’s 1921 ban on women’s football being played at its pitches.

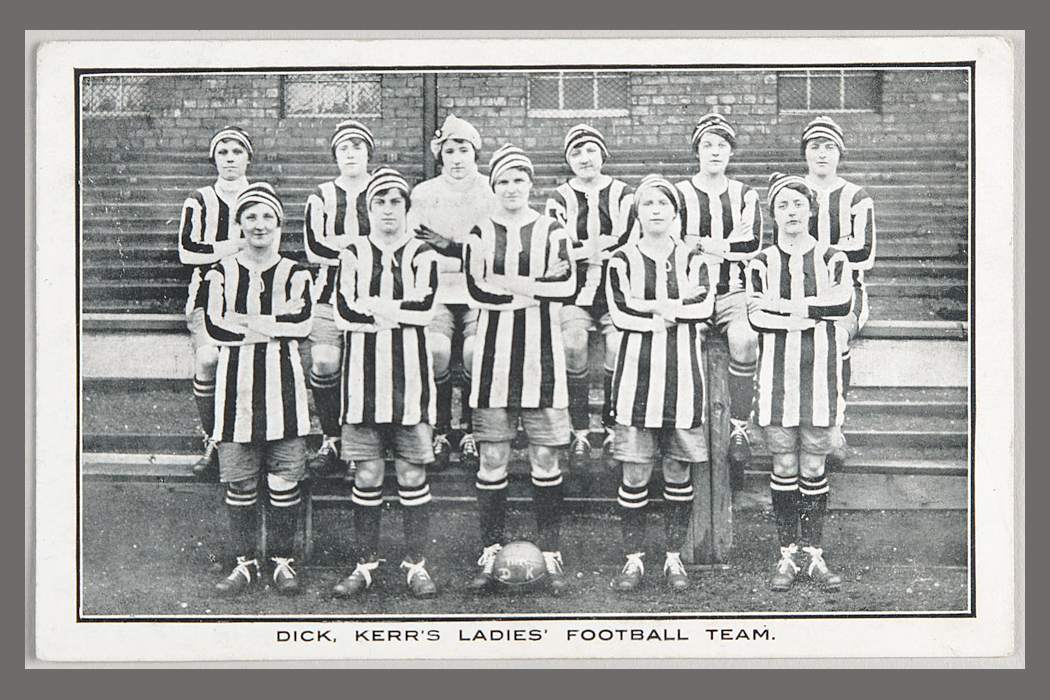

In the fourth section an international perspective on women’s football is given. A chapter is dedicated to the most frequently mentioned football team in the book; Dick, Kerr Ladies, and another, to the pleasure of a Swedish reader, to ‘the first UEFA competition for women’ in 1984. A tournament won by Sweden after beating England on penalties in the final. However, in this section I am missing a chapter about an important and somewhat buried event. That is, a chapter on the “World Cup tournaments” played in Italy in 1970 and in Mexico in 1971, organised by the privately funded Federation of Independent Female Football and both won by Denmark (Boldklubben Femina af 1959), and their significance in forcing football’s power-holders at international and national levels to take action on women’s football. The events offer excellent opportunities to discuss a number of interesting questions about power and monopoly versus free competition. This complex of questions has not been discussed to a sufficient extent in sports history research, but various organizational monopolies has rather been seen as an axiom for national and international sporting competition. It is also reasonable to assume that there was an influence from the football played in Italy and Mexico on English football, after all England participated with a team at both tournaments, defeating West Germany in 1970 before losing to Denmark and failing to beat Argentina and Mexico in 1971.

In the last section, ‘Representing the History of Women’s Football in Culture’, arts projects (here we meet the term heritage-based) as a way to “explore new avenues regarding how academic research can be made accessible to the general public”. It is an interesting and creative element to add to a book about the history of football, but it would have risen to higher level if the initiatives from various cultural creators to present and study the history of women’s football had been looked into by other writers than the people who produced them.

In summary, Histories of Women’s Football in Britain and Ireland is not only a book that utilizes previously inaccessible source material to shed new light on a phenomenon for which interest has increased significantly during the 21st century, but the book also highlights forgotten and/or ignored pioneers. It is only by reading through the original sources that it is possible to challenge the prejudices of previous writers. This makes it well worth spending time reading the book, and the fact that the editors have been somewhat generous when it comes to exercising their editorial prerogative means that any chapter can be read on its own and in the order the reader wants.

Finally, a word of caution not specifically directed to the writers involved in Histories of Women’s football in Britain and Ireland but to all historians in this age of digitized source material. In his book about Sweden and the Holocaust, Klas Åmark warns us not to overestimate what actors at a certain time in history might have known by using old newspapers. Today a researcher, with a few keystrokes, can gain access to almost all the articles published about almost any phenomenon. Historians thus become perfect newspaper readers who see every little news item, down to the shortest pieces of filler, that is, news items that typesetters inserted to fill the gaps on a newspaper page when the “important” articles were set. Add to that the fact that not everything that is printed in a newspaper is true. The historian must therefore make an effort to read old the texts with the eyes of the time, not as someone who know what happened subsequently.[1]

Copyright © Hans Bolling 2026

[1] Klas Åmark, Främlingar på tåg: Sverige och förintelsen. Stockholm: Kaunitz-Olsson, 2021.