Martin Alsiö

Independent Football Historian

On behalf of the government, and indeed our country, I am profoundly sorry for this double injustice that has been left uncorrected for so long.[1]

These are the words used by the British Prime Minister David Cameron to address the hurt and anger among supporters in a well-covered speech in September 2012. He was talking about Europe’s deadliest soccer game ever, infamously known as the Hillsborough disaster in 1989, where 96 supporters of Liverpool FC lost their lives. By the word “double” he was referring to both the inability to bring those responsible to court, but also for portraying innocent supporters as violent hooligans. Soon he was followed by others, representing both the police and the media, and expressing similar apologies. For 23 years they had blamed the tragedy on hooligans. The reason they now all apologized was a national investigation with all parties represented, which had come to the conclusion that no supporter had been responsible. The most thorough research available, Hillsborough: the truth (1999) by Professor Phil Scraton, concludes that the deaths were mainly caused by the police, who were handling security without respecting the capacity of the arena.

Only one month earlier, a Russian court sentenced three members of the feminist punk group Pussy Riot to two years in prison for hooliganism. Their crime was to have performed a political hymn against president Vladimir Putin in a Moscow cathedral. The sentence has been heavily debated and criticized by many, such as Amnesty International, and even by Russian Prime Minister Dmitriy .[2]

Previously, in April, the liberal sports journalist Olof Lundh called the former conservative leader Ulf Adelsohn “a hooligan with tie” in a televised football magazine on the Swedish channel TV 4. The hooligan labeling was also used for advertising the football show in a jocular way.[3] Adelsohn happens to be the husband of Sweden’s Minister of Sports, but his main fault seems to have been the fact that he does not share the political views of the journalist.

Soccer supporters of the 1980s may not appear to have a lot in common with a modern group of feminist musicians or with a retired politician. They are all people of different age, culture, and sex, and are unlikely to have a lot of sympathy for each other. But they do share one common experience. They have all been oppressed by the powers that be, putting the label of hooliganism on them. The grounds for the charges are in all three cases very weak, at best. It is one thing to prove a person guilty of actions as assault, incitement or manslaughter – but a whole other thing to prove a person guilty of adhering to an –ism. Even though this particular –ism – hooliganism – has never had a generally accepted definition, it has not decreased the enthusiasm for using the label. The more unclear the definition is, the easier it is to fill it with whatever one dislikes. It is unlikely that hooliganism will ever have an agreed definition, for the same reason that infidelity[4] was never defined in the European religious conflict in the 17th century, or that terrorism[5] is not defined by the US’ administrations even after 9/11. The vagueness serves its own purpose and gives those with power the tool to oppress those without.

The importance of the word “and”

When creating something like The Hooligans Death List you will always get criticized for mentioning the Accra, Hillsborough or the Kolkata-disasters in the same sentence as hooliganism. And yet, to understand why all those fellow soccer supporters died in these three tragedies is virtually impossible without facing the global fear of this hooliganism. Death, hatred and violence are scary things indeed. But if we meet our fears with only rejection and ignorance we will be overpowered by them. If we eliminate all deadly incidents partly caused by security forces, the presumed good guys, we will only have manipulated our results – and no sustainable solutions can come from lies. Thus, the single most important word in my five essays[6] is and. That is as in the club and its supporters, as in supporters and hooligans, security forces and the people they are placed to protect, or the overall relation between those with power and those without.

To almost every violent sub-group of supporters, soccer is the game to follow.[7] Surely there are some following basketball, ice-hockey and possibly one or two other sports as well. These violent sub-groups are all geographically limited to some countries in southern respectively northern Europe where economic inequality is the greatest in each particular sport. There is no sport anywhere, anytime that has completely avoided relation to violence. This is mainly because all humans have a violent side, or perspective if you will. So why then is soccer the only sport where spectator violence is a distinct theme?

If we look at soccer alone some might suggest that since it is the world’s most popular sport, there will always be some violent people around, simply because of its popularity. For this argument to stand its ground, the second, third and fourth largest sport should also have their proportions of spectator violence. And they simply do not! As long as there are no violent sub-groups of supporters following global sports like cricket, volleyball, cross-country running or the martial arts, the explanation for the presence of violent sub-groups to have something to do with soccer itself!

Nick Lowles and Andy Nicholls have traced the origins of these violent sub-groups in United Kingdom back to the late 1950s or early 1960s.[8] Eduardo Archetti and Amflcar Romero have shown that the first violent sub-groups in Argentina seem to have been formed at around that time.[9] The common denominator of these countries, which still possess the world’s two deadliest soccer cultures, is economic inequality. The increase of international club competitions, the first TV-contracts and the lift of salary caps, as well as a decrease of nationalism, repressive tolerance and respect has all been suggested as motors in the creation of violent sub-groups. The exact relation of possible causes is yet to be studied scientifically.

It is important to notice that there has always been some level of spontaneous violence, as well as some deaths, related to soccer long before the 1960s. The potential of violence is a part of human nature regardless of the economy. Yet researchers like Eric Dunning, Patrick Murphy and John Williams – all focusing on the cultural rather than the economic perspective of British hooliganism – have not been able to find more than one possible incident before 1885. This coincides with the introduction of professional soccer in the UK that very year. As some clubs in the 1960s were able to organize themselves more businesslike, increasing the economical gap between them, so did the supporters of the 1960s organize themselves in a new lifestyle way. A rare few of them chose to defend their club’s honor with force.[10] The increase of football violence in the 1960s can be seen both domestically in Lowles & Nicholls work in the UK, Archetti & Romero’s work in Argentina – as well as globally in my own “The Hooligans’ Death List“.

The Scandinavian experience of soccer hooliganism is not among the deadliest in the world, but forms quite a median example in a global perspective. A widely held theory is that the culture of hooliganism spread throughout the world with English matches being televised, and it is commonly known as the English disease. In Scandinavia these matches were broadcasted by Danish, Norwegian and Swedish public service television jointly from 1969 and onwards. Up until then there are only examples of spontaneous violence in Scandinavian soccer. In the fall of 1970 a field intrusion occurred in Sweden, which is seen as the first form of organized violence according to domestic research.[11] Looking at Sweden alone, this could easily be interpreted as a cultural spread of English hooliganism. However, no other Scandinavians who watched the very same programs were inspired to form violent sub-groups! How can we understand this difference between the Scandinavian countries if we are to stick with a cultural explanation only?

The simplest solution is to look at economic innovations. Sweden had become the first Scandinavian country to lift their salary cap for football players in 1967, which slowly created economic inequality between the teams, and made some spectator groups more easily subjected to violence. Denmark and Norway did not lift the salary caps until 1991, and they never had any problems with organized violence up until then. Since that very year Denmark has rapidly increased the number of organized violent sub-groups.[12] Norway has still managed to keep all supporters together in one and the same supporter club around each team, through an air of togetherness without creating any sub-groups. The introduction of violent sub-groups seems to be closely linked to economic inequality, while the existence of these sub-groups may also be fueled by cultural aspects.

One way to understand the different forms of violence is to place them in the violence triangle developed by the Norwegian peace-researcher Johan Galtung. He extracts three perspectives, structural, cultural and direct violence. The triangle consists of three equally important parts, here represented by equal corner angles. If one corner is split the particular perspective will fall, but it is unlikely to completely vanish until all three are disjointed.[13]

Throughout its history, soccer has had plenty of examples corresponding to each of the corners of the triangle. If we use the causes we found in table 9 in “The Hooligans’ Death List” we will get the following division.

Structural violence is exemplified by capacity not respected, security firing in fear and both locked and tight exits. This is the most frequent form of violence. The main theme here is groups (G). All audiences, whether in sports, theatre or movies, are mirrored by the particular show itself, how it is organized and how the host treats them. When watching individual sports the spectators are far more likely to cheer as individuals or very small groups. When watching team sports, the audience is more likely to form larger supporter-groups around different kinds of cheering. All sports performed in groups or teams will be more open to organized group-violence. Individual sports will be more open to individual violence. Locked or tight gates is not a violent problem if the audience act as individuals and press against them one by one. Security forces are less likely to fire against a single person causing trouble, than if a whole group of people are disturbing the peace. Even not respecting the capacity of the arena might not be a violent problem, if the extra spectators are added individually into different sectors of the arena. It is only in team sports, where the spectators act as groups, where some sub-groups occasionally will run collectively through the gates, or, as at Hillsborough in 1989, collectively are let in on a small sector of the ground, that things will get extremely violent and tragic.

Cultural violence is exemplified by social conflict and reaction to referee. This is the single corner that I personally think is the least hard to break. The main theme here is authority (A) which is a form of cultural violence. I would suggest that there is no sport that so often talks about and points out how some of its followers are unnecessary and undesirable as soccer. This authoritarian behavior is closely linked to the fact that soccer is the “King of Sports”, the team-sport that has the greatest following in the world. Given this fact, it is no wonder that some soccer leaders will think that their club has got more supporters than they need, so why not lose the least undesirable? An authoritarian leadership might have been a successful educational method for creating the world’s most followed sport prior to World War II. But as history teaches us over and over, not being subjected to other people’s opinions, we are destined to create disappointments, conflicts and eventually enemies. When a team becomes popular enough to attract different groups of people, they will surely choose different expressions to support their favorite team. If soccer organizations were run as democracies, the reactions to the sub-groups were likely to be curiousity, including looking of ways to understand the new expressions. Soccer’s authoritarian approach goes straight through the heavy debated president elections in FIFA and other international and domestic organizations, the Europeans’ reaction to the vuvuzelas at the World Cup 2010 or the arrival of yet another plutocrat at one of the top clubs.

One of the most obvious examples of soccer’s authoritarian leadership is how the sport reasons around its referees and the inclusion of goal line technology. Track and field was the first sport already at the Olympics in 1912 to equip the referees with goal line technology. Since then just about every sport has given its refs the benefit of modern technology. The first famously debated “goal or no goal” in soccer occurred in the English FA Cup Final as early as in 1901. Well over a century has passed with lots of controversial goals, and some of the worst supporter behavior ever has sprung out of reactions to a referee’s goal decision. Many of the controversial decisions were followed by polls in the media showing that overwhelming majorities of supporters would like to give the referees the benefit of goal line technology. And each time, the polls are followed up by someone in power saying that 1) the world’s richest sport cannot afford paying for this, and 2) checking for errors could destroy the flow of the game.

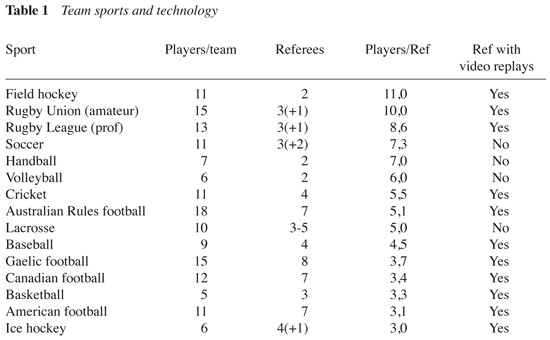

Let us stop for a moment and study how the world’s 15 biggest team-sports have handled the same issue.

The biggest team sports vary from 5 to 18 players per team. At the same time the numbers of referees in different sports vary from 2 to 8. The correlation between players per team and the number of referees is strong. For example, basketball has the lowest number of players on the court and therefor needs a low number of referees, whereas Australian Rules football has a high number of players in the field and therefore requires a high number of referees. When the number of players increases every sport needs an increasing number of well-educated referees with a good eye to keep the matches played fair and according to the rules of the game. Bearing this logic in mind, one would expect the sports with the highest number of players per team also to be keener to help their referees by allowing them the use of video-replays for crucial parts of the game. Surprisingly though, the inclusion of modern technology does not correlate with the number of players per referee. Actually the six sports with the least number of players per referee do allow their referee to have the benefit of video replays. Naturally, this does not mean these referees are more ignorant than their colleagues in other sports without video replays. It only means that their sport respect them enough to allow them the extra control at crucial incidents in the game. It also means that protests are considered serious enough to look into just one more time. This way both teams and supporters will know that if they lose, it is not because of something that the referee did not see. Soccer is one of only four sports with a culture where the flow of the game is considered more important than giving their referees the best possible help. In fact, since soccer is the sport with the highest number of players per referee without benefitting from video-replays – it is most likely the sport which creates most difficult situations for the referees!

Direct violence is exemplified by fans attacking fans, fire and both barrier/wall and whole arena section collapsing. This is the corner that most studies of soccer violence tend to put their focus upon. The main theme here is goals (G), which is a prime cause for direct violence. English historian David Goldblatt has concluded that the key factor for the global attraction to soccer, making it the game with the most people watching and the richest sponsor-deals, is the rarity of goals.

It is the rarity value of a goal that makes it so special […] In a game of flow I would describe a goal as form of an orgasmic punctuation. […] I do not know of any other game that you wait 120 minutes for that ecstasy.[14]

My suggestion is that Goldblatt’s conclusion about the orgasmic impact is applicable to all kinds of supporters, whether they are a part of a violent sub-group of fans or not. There is no team sport with a lower number of goal average, i.e. orgasmic moments, than soccer – and therefore some fans tend to please themselves with a large spectrum of chants, dances, fire-works, flags, messages, songs, and occasionally violent statements. These spectator motions inside the stadiums do require a different kind of constructional preparation than other sports where the action more solely is the game itself and the audience remains seated. A soccer stadium should be constructed for supporters moving, with frequent security checks for damages on barriers, walls, gates and doors to prevent them from collapsing in case of pressure from a large number of people in motion.

The lower the goal average gets – the higher the risk that a controversial decision from the referee will be decisive for the outcome of the game. While sports like baseball, Australian Rules football and handball all have their own controversial decisions, they are, due to the high goal average, seldom decisive for the outcome. The difference in goal average is most likely the key explanation why basketball players often will raise their hand even after an outrageous foul, while their equally professional colleagues in soccer tend to simulate fake hits and kicks quite often. In basketball the advantages for cheating are very small, given the high goal average. In soccer though, the advantages for cheating can be great because of the low goal average. If this has an immediate impact on the players’ performance for how to succeed in sports, than surely it will affect the moral behavior of the many supporters too.

Conclusions on the global scale

I will suggest that Galtung’s theory covers all three key aspects of soccer violence and that any sport trying to copy soccer’s repressive measurements is likely to get the same response from its supporters. We can always expect group-oriented behavior from people following team-sports. When using authoritarian methods to get your measures through, you are always likely to be met by a calm surface and a rebellion underneath. When, as in soccer, most spectators are allowed to watch video replays of difficult situations, while the referees are not, – you are likely to create an acceptance for protests and rebellions. With the low goal average you will not only create a game with lots of excitement and tension. You’ll also create a game where the orgasmic moments are met by an authoritarian attitude from the legislative and excutive powers. The response to this from any opposition will inevitably be organized in groups – and probably violent rather than curious, since that is the tone already set by soccer leaders. On a global scale, every individual fan and sub-group of fans plays minor parts. They can be blamed for local incidents, but not for a worldwide problem. On this level you will get what you ask for.

Together the three corners form the GAG-model (group, authority and goals) which can be interpreted in two different ways. If you are in the upper echelons of the soccer hierarchy, you are perhaps more likely to understand the GAG as a joke, not taking all the problems inside the violence triangle very seriously. If, on the other hand, you’re slaving away at the bottom of the pyramid, you are rather more likely to feel the GAG as just that, a gag, keeping you from speaking up about your personal experiences. If we are to learn anything from Mr. Cameron’s apology for the “double unjust”, it is that we must try to listen to the alleged evil enemies now, and not waste another 23 years. Our hatred feeds and provokes theirs. Why Hooligans Love Their Soccer is dedicated to all people without power in the world of soccer. It is my hope to see you all at a non-violent game soon.

Copyright © Martin Alsiö 2013

[1] BBC News 2012-09-12, The Guardian 2012-09-12 and The Telegraph 2012-09-12.

[2] The Daily Telegraph 2012-11-02 and The Moscow Times 2012-11-06.

[3] http://www.fotbollskanalen.se/allsvenskan/tv-lundh-om-adelsohn-i-fotbollsmandag-en-slipshuligan/

[4] Peter Englund, Ofredsår (Stockholm, 1993)

[5] Noam Chomsky, Skurkstater: den starkes rätt i utrikespolitiken (Stockholm, 2004)

[6] This the second, the first is already published. The third and fourth will focus on Sweden’s most (in)famous violent hooligans as well as Europe’s oldest cheering squad, celebrating their 100th anniversary. The fifth studies solutions to decreased hooliganism by benchmarking successful examples from all continents around the globe.

[7] These violent sub-groups are known by different names in different parts of the world. Mostly they are known as firms or hooligans, but in Europe they sometimes prefer casuals or ultras, and in South America also barra bravas or torcidas. Expressions and relations to violence tend to vary substantially between different groups.

[8] Nick Lowles & Andy Nicholls, Hooligans: the A-L of Britain’s Football Hooligan Gangs (Reading, 2005), Nick Lowles & Andy Nicholls, Hooligans 2: the M-Z of Britain’s Football Hooligan Gangs (Reading, 2005)

[9] Eduardo Archetti & Amflcar Romero, Death and violence in Argentinian football (1994)

[10] Eric Dunning, Patrick Murphy & John Williams, The Roots of Football Hooliganism: An Historical and Sociological Study (London, 1988)

[11] Torbjörn Andersson & Aage Radmann, Från gentleman till huligan? Svensk fotbollskultur förr och nu (Eslöv, 1998) and Lennart K Persson, ”De blåvita invasionerna 1969-1970: den moderna huliganismens första framträdande i Sverige” i Idrottsarvet 1993 (Mölndal, 1993)

[12] Tom Carstensen & Jonas Nyrup, Hooligan: de danske broderskaber (Copenhagen, 2011)

[13] Johan Galtung, ”Violence, peace and peace research” in Journal of Peace Research 1969:6, p 167-191 and ”Cultural violence” in Journal of Peace Research 1990:3, p 291-305

[14] David Goldblatt, The Game at the End of the World, 2010-10-28. The lecture at Pitzer College (California, USA) can be viewed at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1qY8zWK-9Tk